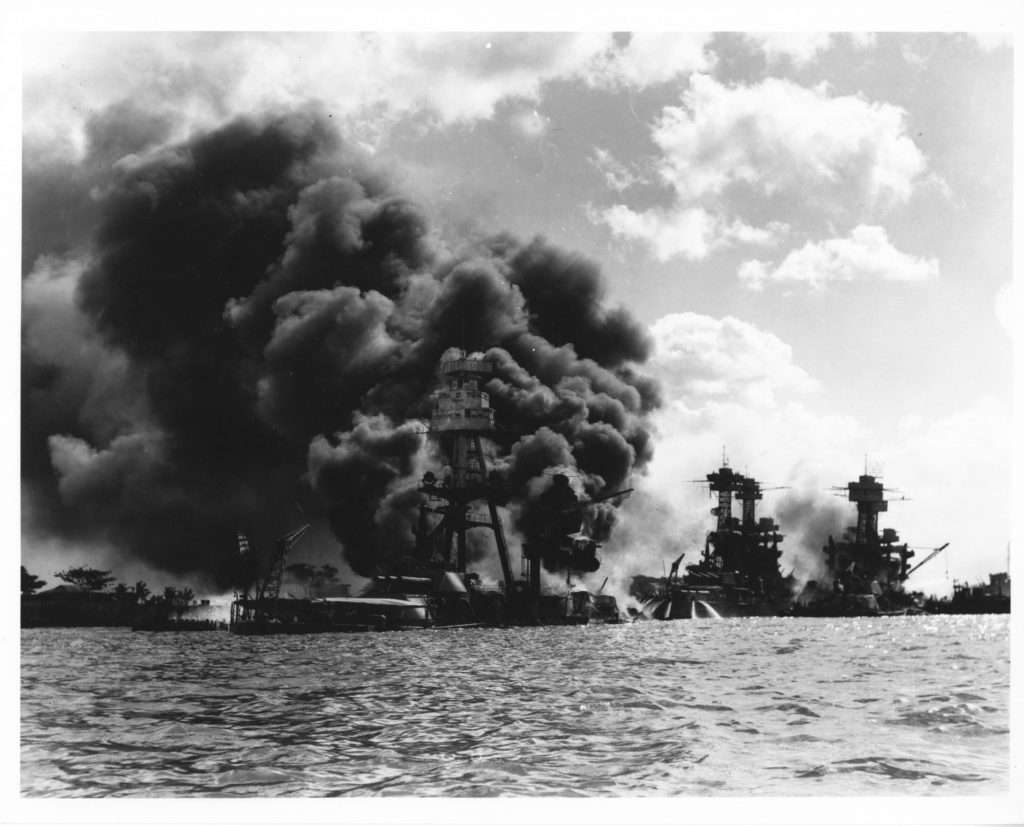

“Tora! Tora! Tora!” Elated in the cockpit of his Nakajima B5N carrier-based torpedo bomber, Capt. Mitsuo Fuchida shouted into his headset, “Charge! Torpedo attack!” the code indicating that, as planned, in defiance of international law, the Japanese attack caught the American Navy by complete surprise.

It was December 7, 1941, 7:55 am Hawaii time. Japanese torpedo planes, high-altitude bombers, dive bombers, and fighters—180 Japanese aircraft in the first wave alone—followed Capt. Fuchida, unleashing 1000s of tons of explosive ordinance on the unsuspecting U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. America’s isolationism was over.

For two chaotic and bloody hours, American forces fought valiantly. What could have been a total loss, was diverted by the heroism of men like Cook  Third Class Dorie Miller. Below decks doing the ship’s laundry when the attack commenced, Miller ran onto the strafed decks of the USS West Virginia. After rendering aid to his wounded and dying comrades, including ship’s commander, Capt. Mervyn Bennion, Miller manned a 50-caliber antiaircraft machine gun, a weapon on which he had no training. Of the twenty-eight Japanese planes shot down, Miller may have hit as many as six enemy dive bombers before he ran out of ammunition and was ordered to abandon ship.

Third Class Dorie Miller. Below decks doing the ship’s laundry when the attack commenced, Miller ran onto the strafed decks of the USS West Virginia. After rendering aid to his wounded and dying comrades, including ship’s commander, Capt. Mervyn Bennion, Miller manned a 50-caliber antiaircraft machine gun, a weapon on which he had no training. Of the twenty-eight Japanese planes shot down, Miller may have hit as many as six enemy dive bombers before he ran out of ammunition and was ordered to abandon ship.

Though none of our aircraft carriers were at rest in Pearl Harbor that morning, American losses were massive. Eight of the nine U.S. Pacific Fleet battleships were either sunk or badly damaged. Eleven other Navy ships were lost, and 188 US planes were destroyed. The loss in human life was greater still. Along with sixty-eight civilians, 2,335 American servicemen died that fateful morning. Many others were badly wounded. The toll would have been unimaginably cataclysmic had it not been for men like Dorie Miller, the first black serviceman to earn the Navy Cross. In 1943, his ship came under heavy torpedo bombardment and sank in the Gilbert Islands. Along with many others, Miller was killed.

“A day that will live in infamy,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt said of the attack on Pearl Harbor as he declared war on Japan, and the United States of America entered WWII.

Fight to the death

We all need heroes. We were wired for celebrating heroic deeds and looking up to people like Dorie Miller. One of my heroes growing up was P-47 World War II fighter pilot, John Hemminger. He lived with his wife and three children on American Lake, a five-minute bicycle ride from my childhood home. I was the neighbor kid who always hung around in the summer, fishing, swimming, and doing wood-working projects in the basement. Along with the stray dogs that attached themselves to kind-hearted Mr. Hemminger, I too adopted the Hemminger family as my own.

John Hemminger was a man of deeds and not words, and so I rarely heard him speak about the war, and never about his role in it. I was forced to piece things together from pictures and from stories others told about his role in that great conflict.

“The greatest catastrophe in history,” Stephen Ambrose called World War II and “the most costly war of all time.” In April 1945, 300,000 Americans attacked the Japanese island of Okinawa, while the U.S. Navy was pounded by 350 kamikaze planes. We lost thirty-six ships. In human life, the casualties were beyond staggering: 49,200 men in one battle. The Japanese lost 112,129 human lives at Okinawa. Still, they fought on.

Germany surrendered in May, but by summer, it appeared that Japan would fight on until there was not a Japanese soldier who remained alive. A full-scale Allied invasion of Japan seemed the only option, but it was an invasion that would have cost 1,000,000 American soldiers their lives. President Truman opted to drop two atomic bombs on Japan in hopes of breaking the enemy’s will to fight to extermination. It was as if the entire nation had become kamikaze flyers.

Fighter pilot greatness

In 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, America joined the war, and can-do men like John Hemminger were desperately needed to fight. He said goodbye to his childhood sweetheart, Edna Mae Firch, and joined up.

The picture I will always have in my mind of him is of a quiet young man in a leather bomber jacket, a shy, boyish grin stretching across his handsome features, posing with his beloved P-47, affectionately dubbed Edna Mae. Though called on to do highly dangerous and daring feats, there was no hint of the cocky, swaggering dogfighter in his looks or carriage.

John Hemminger loved machines. I can only begin to imagine his fascination at first sight of his P-47’s Pratt and Whitney, eighteen cylinder, 2,800 horsepower engine, or the heart-pounding thrill when he first accelerated into the heavens at his plane’s maximum speed of 433 mph.

He was a gentle, peace-loving man, so I particularly wonder what his first thoughts were when he laid eyes on the eight 12.7mm Browning machine guns bristling from the wings of his P-47, a machine engineered for killing. One thing I’m sure of: there was no better cared for fighter plane than his, and likely none more skillfully used for its designed purpose.

John Hemminger was credited with the last P-47 kill of the war. By some accounts, he and the Japanese pilot were slugging it out somewhere over the blue waters of the Pacific, September 2, 1945, while American top brass accepted the Japanese unconditional surrender on board the USS Missouri. The facts are unclear, because John Hemminger rarely spoke about the war, and boasting was something he never did.

What is clear is that John Hemminger, along with a generation of Americans, was a humble servant hero who did his duty, and then, unlike many with whom he fought, he returned home. Bidding farewell to his P-47 Edna Mae, he married his beloved Edna Mae, raised his family, and lived a long, seemingly insignificant life. John Hemminger and his dear wife were not bombastic about their faith in Christ, but few people have more consistently lived out the Lord’s injunction to love their neighbor as themselves. Consequently, their home was a quiet, contented one, filled with stability and service.

In the world’s eyes, after the war, John Hemminger lived an ordinary life; some might have called it boring. But not so to the dozens of missionaries he supported and took fishing when they were home, and whose decrepit cars he repaired, rebuilt, or replaced, often at his own expense. And all done hush-hush, so no one would give him credit for his latest acts of generosity.

True greatness

Jesus told his disciples if they wanted to be great, to become servants. He didn’t say to become great baseball players, or inventors, or CEOs, or powerful politicians, or celebrity pastors, or best-selling authors—or even fighter pilots. “Whoever wants to become great,” Jesus said, “must be your servant” (Matthew 20:26). In my eyes, John and Edna Hemminger were great Christians, because they were great servants.

My hero John Hemminger died of Parkinson’s Disease, December 27, 2006. His wife Edna Mae suffered for decades with Multiple Sclerosis before her home going. But I never heard either of them complain. They bore their trials with patience—even with smiles. Nor did I ever hear either of them speak critical words about others. I think they were simply too busy, in Christ’s name, loving and serving their neighbors. This is true greatness.

“Remember Pearl Harbor!” became the battle cry of the American troops fighting in all theaters. There would have been no D-Day and Normandy Beach landings without Pearl Harbor. Nobody should want a war, but one thing that WWII teaches us is that out of the furnace of warfare emerges the Dorie Millers and the John Hemmingers, and the host of other nameless soldiers and sailors who did what they had to do to serve and love their neighbors, those next to them serving and giving their lives for others in their squad, platoon, company, battalion, regiment, brigade, division, corps, and army.

This post was authored by:

Recent Comments