What does it take for a person to die for the sake of others? What is it that makes a young man of only 22 willing to intentionally sacrifice his own life for the sake of his fellow soldiers? That’s the question I asked myself as I read about Joe Mann. His story came to us from another friend of The Girl Who Wore Freedom, who introduced our team to Byrne Bennett.

The story of Joe Mann began in eastern Washington and ended in Best, Holland. What follows are some highlights from those stories told to Byrne by his mother—some are the typical antics of a mischievous middle child of a large farm family, and some are extraordinary, revealing the character of a young man who would ultimately sacrifice his very life.

Family Memories

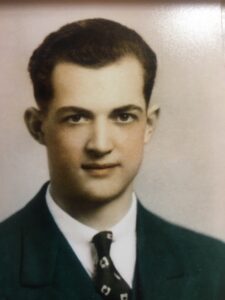

As a boy, I was fascinated with the stories about an uncle I never met – my mom’s brother Joe. He was a war hero that died at the age of 22 in Operation Market Garden in Best, Holland. My mother was the second youngest of nine children, and Joe was fifth, in the exact middle. In my childhood mind, I assumed that all those who went to war died. I thought that was part of the deal since his story loomed so large in my young imagination. Joe’s Purple Heart and Medal of Honor were kept inconspicuously in boxes in a magazine rack by the couch. I used to take them out of the boxes and wear them until my grandmother scolded me.

My mom often told me stories of her older brother Joe, creating a larger than life character in my mind. Three childhood surgeries didn’t slow him down; he endured them with a good attitude. He had a great mechanical mind and could often be found whistling in the barn, hands and mind busy doing anything from fixing farm machinery to making wooden toys and crystal radios as gifts for his siblings—even experimenting with explosives. Though many of his teenage injuries were due to recklessness, his disregard for his own safety must have been one of the things that eventually made him a hero on the battlefield.

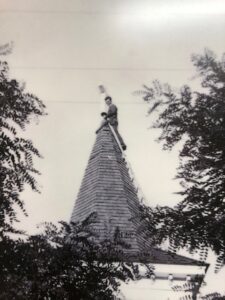

The other important fact about Joe’s story is that he was the first to attend church in my mother’s family. When a new Lutheran pastor came to town, he took an interest in Joe, a teenager who raked leaves and chopped firewood for the widows in town and helped paint the church and most certainly added life to gatherings of the local youth group. When the new cross arrived for the church, it was Joe who climbed the steeple to place it. As a Christian, I trace my Christian heritage to him, and my mother was always grateful to him for introducing her to Christ.

The other important fact about Joe’s story is that he was the first to attend church in my mother’s family. When a new Lutheran pastor came to town, he took an interest in Joe, a teenager who raked leaves and chopped firewood for the widows in town and helped paint the church and most certainly added life to gatherings of the local youth group. When the new cross arrived for the church, it was Joe who climbed the steeple to place it. As a Christian, I trace my Christian heritage to him, and my mother was always grateful to him for introducing her to Christ.

In the fall of 1941, during his senior year of high school, this loyal, caring, and scrappy risk-taker broke his collarbone in a football game. Though injured, he refused to stop playing as he felt his buddies needed him. After the game, my grandfather drove him to the hospital in Spokane, where a metal plate was inserted into his collarbone. This event not only impacted his ability to fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming a pilot but also foreshadowed the way his life would end on the battlefield three short years later.

Army Training

After graduation, Joe went to the Recruiting Office of the Army Air Corps, hoping to follow in his older brothers’ footsteps to become a pilot. He failed the physical due to “retained hardware,” the term used for surgically implanted steel. Determined to serve his country, he then volunteered for the Army paratroops. I guess he figured if he couldn’t fly the planes, jumping out of them in service to his country would be the next best thing. He was sent to Camp Toccoa, Georgia, where he was assigned to the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR). As an original “Toccoa Man,” he trained alongside the “Band of Brothers” of Easy Company.

The beginning of his short army career was rough, and, as with many young men, Joe clashed with his sergeant, resulting in Joe’s transfer to the 502nd PIR. On his last night with the 506th, he and his buddy Jim sat on a dumpster commiserating over the transfer. According to Jim, the last words Joe said before his transfer were, “You haven’t heard the last of me.”

Joe spent the next year training in England with the 502nd. Prior to D-Day, he was one of many men injured in their final training jump, causing him to miss the invasion of Normandy. A few months later, however, he saw his first day of battle as an American paratrooper in Operation Market Garden. His only jump with the 101st Airborne Division was on September 17, 1944.

Operation Market Garden

Joe’s task was to guide 44 men from the drop zone to the Wilhelmina Canal to secure the bridge. Joe led his platoon through a forest, around a swamp, and over a dike as enemy machine guns repeatedly fired upon them. In the darkness, the men approached their objective unaware that hundreds of German soldiers lay in wait. Joe and his lieutenant crawled along the canal and saw the bridge’s silhouette in the moonlight. Unbeknownst to them, they had crossed the German front line. For forty minutes, they lay on their bellies as a German sentry circled them, his boots inches from their faces. Joe was ready to knife the guard, but his lieutenant objected, afraid it would draw attention to them. The rest of the platoon hunkered down behind them called out in concern, distracting the guard and allowing Joe to knock the guard unconscious. They retreated, dodging machine-gun fire from all directions.

The next morning on September 18, 1944, the Germans discovered the platoon’s vulnerable position and opened fire, killing 29 of the 44 men. Joe grabbed a bazooka and searched for the heavy artillery that had decimated his buddies. He located the 88 mm anti-tank gun and a large cache of ammunition and destroyed them both. Standing in an open field, he shot the enemy one by one, killing at least six Germans. Joe was wounded four times in his upper body and both arms. He staggered back to his platoon and was mistaken for the enemy by American Thunderbolt airplanes dropping from the clouds and opening fire. Despite his injuries, Joe finally made it back to his platoon, where medics bandaged his arms to his body like a straight-jacket. He trembled violently, having gone into shock. Joe refused to be placed with the other wounded, however, insisting that he could still make a contribution. Joe located a trench holding fighting men and requested to stand guard so that they could sleep.

At dawn, the men awoke to gunfire. Joe had wriggled out of his bandage and, though he was badly wounded, was shooting his rifle at approaching Germans with one arm. Soon potato masher grenades pummeled into the trench. The men scrambled to throw them out. One exploded, further injuring Joe. Several more landed in front of him. With his arms now useless, Joe yelled to the men, “I’ll take this one,” and threw his body on the grenades. Looking into his lieutenant’s eyes, he said, “My back is gone,” and died.

The six men whose lives Joe saved later said he had been their heart and soul. After Joe was killed, they lost their will to fight and immediately surrendered. The survivors all said Joe was the bravest man they’d ever known.

Joe’s story of heroism was nearly lost as the men he’d saved made a pact not to recount the details of the battle in their interview with Army Historian SLA Marshall a few days later. Marshall sat them down in a Dutch barn to get an explanation as to how they held off hundreds of Germans with just a few men. They hemmed and hawed and gave conflicting accounts, until Joe’s buddy James Hoyle looked at his lieutenant and said, “I have to tell the truth.”

The men explained that they’d been deceptive because they were embarrassed that so many men had been killed, some actually ran away, and the rest were finally captured. Hoyle said they were ashamed of these things, but he had to tell the story of one man who fought with them. Soon the floodgates opened, and the men told Marshall what Joe had done during the three-day battle. Marshall obtained affidavits from the men and recommended Joe for the Medal of Honor. If Hoyle hadn’t spoken up, Joe’s story would have never come to light. Years later, Brigadier General SLA Marshall said in a speech:

“It was always Joe Mann leading the fight. It was Mann who kept getting hit because he took the worst chances. He did not know how to quit. Such valor is not born by accident. It comes mainly from a tremendous caring for one another, and is the result of the land and the love which made him possible.”

For his actions on September 17-19, 1944, Joe was posthumously awarded five Purple Hearts, a Bronze Star with Valor, and the Medal of Honor.

Remembering Joe

Like the people of Normandy, the Dutch citizens have continued to honor the soldiers who fought to liberate them from four years of the German occupation. Each September, the town of Best honors Joe’s memory and the part he played in Operation Market Garden. The people of Best formed a Joe Mann Club for the youth and, in 1956, dedicated the Joe Mann Monument near where he was killed. A giant figurine of a pelican graces the top of the monument as a symbol of self-sacrifice. According to mythology, the pelican will tear the flesh of its own breast to feed its young.

Joe has been honored here in the United States as well. In Joe’s hometown of Reardan, Washington, plans are underway to establish a memorial. This September, the Daughters of the American Revolution designated his birthplace a historic site. Perhaps more notable than this, however, is the inscription on the (now defunct) Joe Mann Army Reserve Center in Spokane, Washington: “Greater Love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.”

As I reflect on Joe’s story that Byrne shared with me, I have to wonder again: what does it take for a person to die for the sake of others? It’s love that leads us to service and sometimes to sacrifice. It is love that motivated Joe and thousands of other soldiers like him to sacrifice heroically. Some of those stories of sacrifice are featured in our film, such as Bob Fressen and Bob DeVinney, who survived extreme cold during the Battle of the Bulge, and Willie Kellerman, who escaped a German prison camp on a stolen bicycle. It was love that motivated Simone Renaud to visit hundreds of soldiers’ graves and send letters, flower petals, and blades of grass back to their grieving families. It is also love that motivated Marie Pascal to sacrifice her time and attention to care for Charles Shay, a veteran who needed a great deal of care. It’s love that continues to motivate hundreds of modern French families to visit soldiers’ graves to this day.

This same love can motivate each of us to die to ourselves in many smaller ways, such as sacrificing a bit of our time and attention to listen to our veterans’ stories. We are not all called to the battlefield, but we can all can sacrifice a bit of ourselves every day. As we celebrate our veterans and remember the sacrifices of those like Joe Mann, who gave their very lives in our nation’s service, I think it right that we give pause to honor the love that fueled the sacrifice of so many for the freedoms we enjoy today. May their legacy live on as we honor them today.

This post was authored by:

Byrne Bennett

Byrne Bennett

Guest Author for The Girl Who Wore Freedom

Byrne Bennett was raised in Salem, OR, and graduated from Chemeketa Community College, Willamette University, Portland State University, and Western Oregon University. He was employed as a Federal Agent, working in Alaska and then Washington State, before retiring in 2014. He and his wife Denise live on a small wheat farm in Reardan, WA, with their horse, goats, chickens, dogs, and rabbits. Byrne has visited the site of his uncle’s death in Best, The Netherlands, on six occasions, and is nearing completion of a historical/fiction book about his uncle entitled, “A Greater Destiny.”

Laura Browning Priebe

Laura Browning Priebe

Writer for The Girl Who Wore Freedom

Laura is fascinated with stories – reading, viewing, and listening to people’s stories. Both of her grandfathers served in WW2, her father is a Naval Academy grad, and her brother is a retired Army Lieutenant Colonel who served 20+ years, including service in Afghanistan. Compared to most of her family, she doesn’t consider herself a history buff, but once history is connected to the stories of real people, she’s hooked! She lives in Southeast Indiana with her husband and family.

Recent Comments