This weekend The Girl Who Wore Freedom team in the United States and France paused to commemorate the 77th anniversary of the D-Day landings. We were reminded there are still so many stories of service and sacrifice from that day that remain untold. In honor of all the men that came ashore that day we are pleased to share the story of Wiliam Manning of the Navy’s 81st Construction Battalion as told by his son Donald.

Like countless millions of others, I am a child of the Greatest Generation, the son of a combat veteran of the Second World War. When these warriors returned home, having defeated fascism and imperialism, they set about creating a “normal” life for themselves as they were able: a job, marriage, a home, and creating a family that resulted in the “Baby Boom.” The seventh of eight children, I arrived in 1961 as the boom had begun to recede, ending by most accounts around 1964, the year the youngest child in my family was born.

There are precious few members of the Greatest Generation remaining, and their numbers continue to dwindle by the day. Both of my parents are now gone, my mother passing at age sixty-one after a long and cruel battle with early-onset Alzheimer’s. And my father, seventeen years later, passing too young at age seventy-seven. Not unlike his comrades in the crusade to rid the world of tyranny, my father was reticent about his experiences during the war: the blood and suffering of D-Day, and months later, the kamikaze attacks and flamethrowers of Okinawa. The men who returned from the horrors of war did not want to burden their families with their memories. For most of them, those memories were their private pain, haunting shadows of events they had survived when they were young and were anxious to move beyond. Many, when they died, took their stories with them. I am blessed that my father shared one special story with me, a story he could tell because it wasn’t about death and destruction. It was a story about life. The story of the baby who lived.

Unlocking Memories

On June 6, 1944, William Manning, the twelfth of thirteen children born to Irish immigrants who settled in South Boston, Massachusetts, landed on Utah Beach with the United States Navy’s 81st Construction Battalion (NCB). He was just five weeks past his nineteenth birthday. More often associated with the building of docks, airfields, bases, and infrastructure during World War II, the Construction Battalions (more commonly known by their nickname: Seabees) also played key roles in battles that involved amphibious landings. The Seabees brought heavy equipment, vehicles, and other vital war matériel, including ammunition, rations, and medical supplies, from ship to shore.

I knew my Dad had been a Boatswain’s Mate Second Class on one of the motorized flat-bottomed barges (Rhino Ferry in Seabee lingo) that brought heavy equipment from massive navy vessels to the Normandy beaches as the invasion was underway. I also knew that in those early days of the invasion, in addition to disgorging a steady stream of matériel onto Utah’s sands, the 81st worked to ensure that that the push beyond the beachhead was secure. And I came to know the vague story about a baby born in a world turned upside down, a baby who had lived at a time when so many, so nearby, were dying.

I knew my Dad had been a Boatswain’s Mate Second Class on one of the motorized flat-bottomed barges (Rhino Ferry in Seabee lingo) that brought heavy equipment from massive navy vessels to the Normandy beaches as the invasion was underway. I also knew that in those early days of the invasion, in addition to disgorging a steady stream of matériel onto Utah’s sands, the 81st worked to ensure that that the push beyond the beachhead was secure. And I came to know the vague story about a baby born in a world turned upside down, a baby who had lived at a time when so many, so nearby, were dying.

In 1987, a year after my mother’s passing, Dad called and asked if I could find the time to travel to Normandy with him. At age sixty-two, it would be his first trip back to the beaches that he had landed on as a teenager. Fortunately, I was able to accompany him.

He wanted to travel not just to Normandy, but to all the places where his unit had spent time in Europe. Our first stop was Helensburgh, Scotland, where the 81st Construction Battalion had first arrived overseas in the late summer of 1943. From there we went to Penarth in Wales, where Dad’s unit had built facilities needed for housing and training and had practiced the amphibious landings that would ultimately take place under withering enemy fire. Forty-three years had passed since Dad had seen Helensburgh and Penarth, and the memories came flooding back—about young Americans and British beer! Finally, we got ourselves to Portsmouth, England, which had been his Battalion’s middle-of-the-night jumping-off point for Normandy in the early hours of D-Day.

From Portsmouth, we took a ferry across the English Channel for a one-night stay in LeHavre, France. The next morning, we caught a bus to Caen, the city beyond Omaha Beach that was virtually destroyed during and following the invasion. From there, we caught a train to Carentan, a city closer to Utah Beach. Our travels had not been planned in great detail, and we discovered when we arrived in Normandy that we had overlooked an important detail. It was Sunday, and the banks were closed on Sundays. These were the days before ATMs. I had British (and American) money in my pocket. And credit cards. But no French francs. As we stepped off the train in Carentan, I realized we had a problem.

Utah Beach

I had planned to get a cab out to the beach, but I would need cash for that. What to do? I dashed over to the ticket window at the train station. The clerk was not interested in my plight. I frantically looked around and spotted a driver leaning against the side of his cab, waiting for a fare.

I had studied and developed a passion for French in high school, and fortunately, it was at least passable enough for me to explain our situation. I said, apologetically, that I had no French francs. The driver, Etienne, shrugged, looked off into the distance, uninterested…until he heard the words, “I’m here with my father; he wants to see Utah Beach where he landed on D-Day.”

Etienne looked at Dad standing hesitantly nearby, opened the door to his cab, and waved the two of us inside, saying just one word: “Utah.”

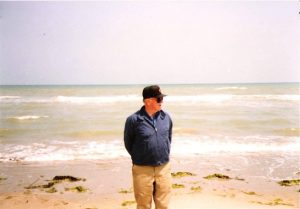

The beach was empty that day. We made our way down the dunes and took our time getting across the vast expanse of soft white sand to the edge of the shingle where the footing is a bit easier. I was taking in the stunning beauty of the French coastline, lulled by the rhythmic pounding of the waves. But from the corner of my eye, I was watching my Dad. He gazed out to sea for a long time, his head moving ever so slowly as he took in the entire horizon.

The beach was empty that day. We made our way down the dunes and took our time getting across the vast expanse of soft white sand to the edge of the shingle where the footing is a bit easier. I was taking in the stunning beauty of the French coastline, lulled by the rhythmic pounding of the waves. But from the corner of my eye, I was watching my Dad. He gazed out to sea for a long time, his head moving ever so slowly as he took in the entire horizon.

Finally, he turned and scanned the beach and the bluffs where seagrass waved gently in the breeze. I could not imagine what he was thinking…or seeing. Surely, in his mind’s eye, he was reliving that day. In the dark early-morning hours, Dad and his buddies had detached their barge from the ship that had been towing it and chugged forward to the bow of the giant transport. The cargo door had been lowered. Working as fast as they could, they transferred cargo from the vessel’s hold: tanks, trucks, half-tracks, howitzers.

Meanwhile, all around them, the sky exploded with flashes that for seconds at a time turned night into day, and the earsplitting chaos of battle filled their ears–thundering artillery, incessant gunfire, men shouting and screaming, the whining of shells, all too close.

When the Rhino reached the beach, the first vehicle off on this run, and on every run, would be a bulldozer. Secured to upright stanchions by chains, its job would be to drag the barge well up onto the beach. But on Utah, there was an unforeseen complication. German artillery—the notorious 88s—had pounded the beach with shells angled to create giant craters. When the first bulldozer rolled off Dad’s barge…it simply disappeared into one of those shell holes. Disappeared. A minor setback. Seabees being Seabees, the men quickly figured out how to rescue the bulldozer (and its driver) and kept right on with their work, all the while under shell fire.

Seabees of the 81st Construction Battalion. 1944. William Manning is in the front row, second from the left.

The work of the D-Day landings continued around the clock as the days passed, danger ever-present. Eight days after the landing, on June 14th, Dad’s shipmate, Marvin Krull, “a nice kid from Chicago,” was hit by shellfire and killed. Marvin’s sudden death left Dad and his crewmates stunned. All of them would wonder for the rest of their days, “Why him? Why not me?”

As I was thinking about all this, Dad just stood there. Quiet. Looking. Finally, he shook his head and spoke softly, more to himself than to me, “Those poor boys.”

And then, “I have to find the baby.”

I was befuddled. “What baby?”

“The little girl. Sea Bee.”

A New Life

Dad explained. For days and weeks after that initial landing, he and the others continued to unload cargo from the big cargo-carrying vessels, at first by Rhino Ferries, and once the beachhead was secure, from Seabee-built causeways. The men of the 81st were bivouacked near the towns immediately proximate to Utah—Sainte-Mère-Église, Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, and Pouppeville.

On the morning of July second, a young boy came through the lines asking if there was a doctor. A baby was being born, and there was no doctor or nurse in the village to help the young mother. Lieutenant Commander Anderson, the battalion’s medical officer, dispatched Lieutenant Douglas Butman, the member on his staff with the most obstetrics training.

By the time Dr. Butman arrived, the baby girl had already been born. But his help was still needed and much appreciated. Both doctors from the 81st continued to check in regularly on the new mother and her infant. The new parents—Henri and Marie Fouchard—were deeply grateful for the Seabees’ help and for what they hoped would be the liberation of Normandy. So, to honor these Americans, they gave their newborn daughter a name unheard of in France—Sea Bee.

The men of the 81st Construction Battalion had seen so much death in the previous few weeks. Here was a new life. Informally, unofficially, and amongst themselves, they decided to adopt their namesake and do something memorable for this child brought into the world in the midst of war. So, they established a trust fund for her education. Over the years, the story passed into legend on both sides of the Atlantic. Sea Bee stayed in touch with several of her American fathers. And when she married Claude Ruault, the leadership of the U.S. Navy Construction Battalions sent a silver tray engraved with the familiar fighting bumblebee insignia.

The men of the 81st Construction Battalion had seen so much death in the previous few weeks. Here was a new life. Informally, unofficially, and amongst themselves, they decided to adopt their namesake and do something memorable for this child brought into the world in the midst of war. So, they established a trust fund for her education. Over the years, the story passed into legend on both sides of the Atlantic. Sea Bee stayed in touch with several of her American fathers. And when she married Claude Ruault, the leadership of the U.S. Navy Construction Battalions sent a silver tray engraved with the familiar fighting bumblebee insignia.

Kindness Remembered

“I have to find her,” Dad insisted, as we climbed back up over the dunes. We knew we had returned from 1944 to the present when we saw Etienne leaning against his cab just as he had been when we first spotted him at the rail station in Carentan.

“Where else would you like to go?” Etienne asked. We weren’t quite certain. I asked if he knew of Sea Bee Fouchard. He did not know of her and did not know how we could possibly find her but he had other ideas. Etienne took us to the Utah Beach Museum (Musee du Debarquement) and to the American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach.

Watching Dad walk amongst the headstones of those who never made it home was overwhelmingly painful, and the image remains seared in my memory. Leaving the cemetery, I knew he had seen enough, and the time had come for us to get to Cherbourg to catch the ferry back across the Channel to England. However, our lack of planning being what it was, we hadn’t figured how we were going to get there.

“Do not worry,” Etienne said. “I will take you to Cherbourg.” He got us to the ferry terminal in plenty of time. At the terminal, as he was taking our bags out of the trunk, I said, “Please give me your address; I must owe you much more than I have on me.” He said, “You owe me nothing.”

Etienne was about ten years younger than my Dad, making him old enough to remember when the Germans marched into his village. Speaking of the Wehrmacht, he said, “The soldiers in the gray uniforms, they missed their homes and families, and many of them were kind to the French children. They would give us candy.” This was not to suggest that the French accepted the occupation of their country, but that the soldiers in gray had shown them some humanity. His tone changed when he spoke of the Schutzstaffel – the dreaded SS. “But when the black boots came,” Etienne told us, “We were terrified. We had seen them do terrible things. We ran and hid under our beds.” He paused.

“Then, finally, the Americans came. We were surrounded by men in uniform who were kind. There were no more black boots. We no longer had to hide under our beds.” He turned to my father, spoke in French, and I translated: “You, sir. You were one of those Americans. This day. This is my thank you.”

On the ferry back to England, Dad wondered aloud about Sea Bee. “She would be forty-three years old. Is she still alive? Does she have a family? Has she moved away?” Seven years later, we would get the answers to those questions.

Come back next week for the rest of William Manning’s story.

Recent Comments